Looking east

Lost to the West

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that an outfit that calls itself The Byzantine Review thinks highly of a book about the Byzantine Empire. Not surprising unless, like me, about all you learned on the topic was that “Rome fell and the barbarians ran all over everything ushering in the Dark Ages, and then they built churches without flying buttresses and that made it even darker, and thank goodness the Renaissance came along and saved us all.”

Sound familiar?

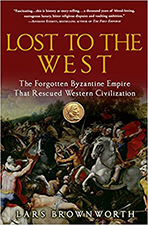

The book in hand is Lost to the West by Lars Brownworth, which tells the story of the Eastern Roman Empire from the founding of the city of Constantinople in A.D. 330 until its fall to the Turks in 1453. The place was built by the Roman Emperor Constantine, and if you’re guessing there was some ego involved, you’re right. And of course the city still exists, now named Istanbul…which is the true reason you can’t go back to Constantinople. The city was built on the site of a small, previously-existing town called Byzantium, and just why Constantine built it has a great deal to do with Roman politics.

By the fourth century, Imperial Rome had become bogged down in civil war, with a rapid succession of emperors propped up by one faction or another, only to be assassinated or overthrown. During times of national unrest the general population suffers; and in Rome that led to various philosophers and mystics proposing alternatives to the traditional pagan gods, whose good wishes seemed to have deserted Rome. One of those alternatives was Christianity, which by the fourth century had grown to include a significant portion of the population. A portion that included much of the military…in the story I was taught, General Constantine saw a flaming cross in the sky (it was night) with the legend, “By this you shall conquer.” Which, according to the story, led him to convert himself, the army, and the empire to Christianity, right there on the spot. I would never question the authenticity of anyone’s religious conversion…but it is also true that Constantine found himself leading an army that was largely Christian. Constantine was not in line for the imperial throne, but when the army figured out he was one of them, a Christian, the Senate’s guy became irrelevant and the army made Constantine emperor.

All of which honked off the aristocracy back in the city of Rome to no end. Most of them were pagan (Constantine made Christianity legal in Rome, but did not make it the state religion) and none of them liked having some army brat push his way to the front of the line, much less get himself made Emperor. Constantine decided that Rome was too full of old history and old religions to move past the past, and he established a new city, named after himself of course, as the new capital. It really isn’t that unusual a move: recall that in the U.S. the federal government first met in New York, which was the capital until the District of Columbia was built, then they moved it. In just that way, Constantine built his new capital and moved the Roman national government there. When the city of Rome (and with it, the Western part of the empire) fell, the residents of Constantinople didn’t stop seeing themselves as Roman any more than I would stop seeing myself as American if the Canadians ever capture New York. And so they remained Roman, residents of the Eastern Roman Empire, to themselves and the world; the term “Byzantine” is a 19th century construct that would make no sense to them.

Lost to the West accomplishes the near-impossible, summarizing a great deal of history in a slim volume. The problem with the Eastern Roman Empire is that it didn’t fall until a millennium after the Western Empire, not until 1453. The challenge for any writer is to find a way to compress that many years into an arc that makes any sense for a reader, and I confess that by the end of Brownworth’s admirably brief volume, I was starting to glaze over a bit in the “OK, these guys conquered those guys who then conquered them back again” ilk.

But with a that much history to work with, there are some great stories along the way.

Take, for example, one of the earliest backup groups, the Varangians. In the tenth century Emperor Basil II had allied with the Slavs, and in return for marrying Basil’s sister (the Roman aristocracy were horrified), Tsar Vladimir sent Basil 6000 Norse warriors, all over six feet tall, skewing blonde, and all handy with a double-headed axe. Basil was so thrilled he made them his personal imperial guard, a post they then held for nearly 300 years. He also gave them one of the oddest “out of the box” employee benefits ever: in exchange for unwavering loyalty to the emperor, the Varangians at his death were allowed to enter the treasury and cart off as much gold as each man “can comfortably carry” as his personal reward. Loyal they remained, although you have to wonder if that had anything to do with the high turnover in emperors after Basil.

Basil himself was hands down my favorite Byzantine Emperor. Starting with his full name, Emperor Basil II the Bulgar Slayer. (I’m not making any of this up.) Not only did he put down a rebellion in Bulgaria, he regained much of the Empire’s lost territory, overhauled the system of law, and funded large programs of education and the arts. Also invented the fork: the earliest anyone had seen of a fork was in 1024 when a princess made a show of eating with one at Basil’s court. It was a Kardashian moment, and soon anybody who was anybody was using a fork. Regrettably for such an industrious and detail-oriented fellow, he gosh-darn it just didn’t leave any heirs. Not even illegitimate ones. The author doesn’t speculate on why, but let’s face it: things were just so busy. Especially with the big fork roll-out and all. Basil left a glittering empire and re-established the legitimacy of its government, but Bosworth’s final comment has him as “splendid but remote – surely the loneliest figure ever to sit on the Byzantine throne.” Sadly, he may be right.

The history of the Eastern Roman Empire is the story of loss and regrouping, always smaller and weaker each time it regrouped. The end, in the 1440s and 1450s, was operatic, involving among other things efforts to reunify the Roman and Orthodox Catholic Churches (including a dandy slap-down of increasingly old manuscripts as part of the Council of Florence). By then the Eastern Roman Empire had been reduced to the city of Constantinople itself. The final blow, the Deus ex Machina, was the cannon: ballistics were a new technology that made Constantinople’s millennium-old walls inconsequential. The last Romans knew the end was coming and worked to move books, manuscripts, and learning to the capitals of Western Europe which were now the safest place for them.

Constantine was consciously looking East when he founded Constantinople, to what I grew up calling Asia Minor. I think it is in that sense that Lost to the West takes its title. The Eastern Empire lost twice, once in its territorial ambitions to hold Asia Minor; and then, more profoundly, when its history became uninteresting to the Renaissance. For most of us, the history of the Byzantine Empire truly is lost.

Copyright © The Curmudgeon's Guide™

All rights reserved